The pleasures of rock climbing and the pleasures of philosophy turn out to be strangely similar. Most non-climbers have the wrong idea about climbing – it is, in the popular imagination, a particularly thuggish way of courting death. Before I’d actually tried it, my mental image of climbing was some kind of vague blend of pull-ups, screaming and gargling Red Bull. But it turns out that rock climbing is a subtle, refined and often hyper-intellectual sport. It’s solving puzzles, with your body and mind. It’s about getting past cryptic sequences of rock, through a combination of grace, attunement, cleverness, and power.

Climbers dream of the perfect “project” – a climb that you work on, over days and weeks. At first, such a project might seem utterly impossible. The holds are too small, or in the wrong place, or impossibly far apart; the wall is too overhung, or too blank. But slowly, bit by bit, you figure out a sequence of moves that just might get you through. Place your left foot there, and balance over just so. Flip your left hand so you’re pushing down against that ridge of rock, leaning down on it like you’re in a yoga triangle pose. Then you can reach high with your right hand and take hold of a tiny pocket. Step high and then flip your hand in the pocket, so you can lean the other way. Through care and attention, the impossible slowly becomes possible. You learn the holds, you learn the moves, you learn where to throw in all-out effort and where to relax for a moment, you train your body, until one day it all comes together and you dance your way up that wall.

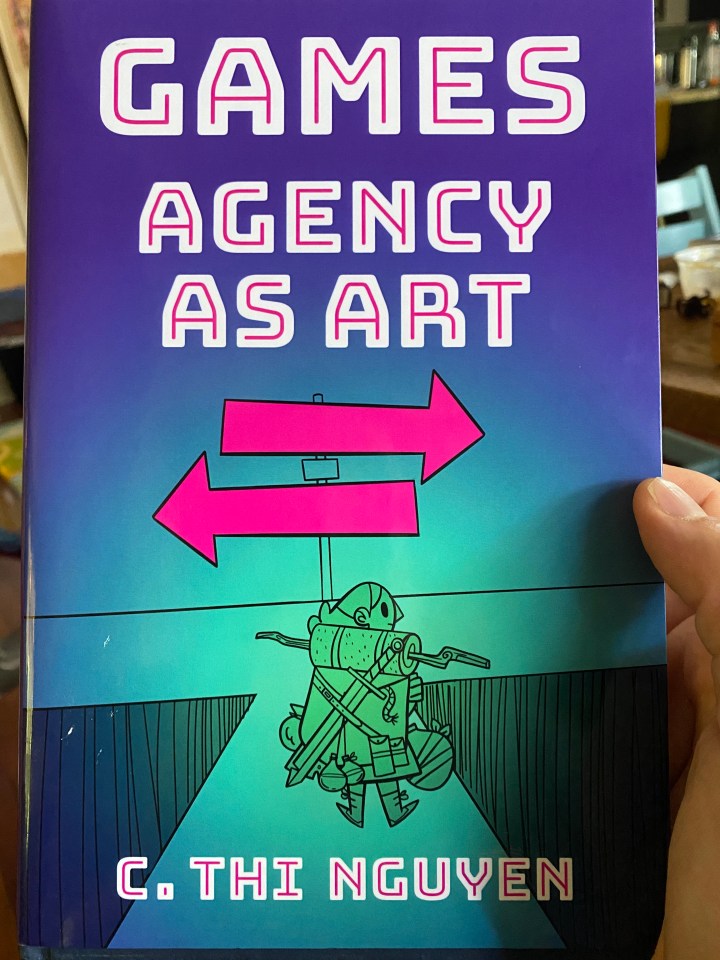

Dana Le/Flickr

And dancing, I think, is exactly the right place to start to understand the aesthetic dimension of rock climbing. So let’s start there: climbing is something like dance – not just in skill, but in aesthetic reward. You can hear the similarity when you listen to some climbers talk about their climbs. They talk about climbs with nice movement, with good flow, with interesting moves. They’ll talk about ugly climbs, beautiful climbs, elegant climbs, gross climbs. At first you might think they are just talking about the rock itself and how it looks. And sometimes they are; every climber loves a clean crack up a blank face, or bold jutting fin to climb. But if you interrogate a climber, and watch as they explain where the beauty in the climb is – with arms out, legs in the air, imitating the odd precise movements of the climb – you’ll figure out that what so many of them care most about is the quality of the movement – about how it feels to go through the rock, about the glorious sensations in the body, and the subtle attention of the mind.

So let’s start with dance. Barbara Montero, a philosopher of dance, has made a convincing case that the central aesthetic experience of dance involves a dancer’s proprioceptive sense of moving through space and feeling that movement as beautiful. We don’t just appreciate dance visually; we can feel it in our muscles and neurons. As a consequence, she adds, the best people to understand the aesthetics of dance are the dancers themselves, and people in the audience who have danced – who can imagine their way more precisely into how it must feel to move that way. The beauty of dance is a beauty of embodied movement.

When I think back to my favourite climbing experiences, what I can remember most precisely is the feel of the movement, the sense of gracefulness, of being able to move with precision and economy and elegance. That movement quality is something I savour, that I daydream about, that calls me back. And sometimes that movement quality is embedded in something dramatic. It has a relationship with difficulty. Some of the most perfect climbing moments are those when I was exhausted, maybe bleeding a little, when my fingers were raw, but I forced my mind quiet and calmed my head and then pulled through, forced my trembling limbs to calm, and reached somewhere inside myself to find that elegance, that precision, that lovely movement.

So climbing is like dance, but not exactly like dance. Climbing is graceful movement that always serves a well-defined task-oriented purpose. You’re trying to get to the top, and often the harder that journey is, they better. And climbs don’t just allow graceful movement; they sometimes require it; they’ll punish you and throw you off the rock if you’re careless. The economical movement in climbing arises in response to a set of very specific demands. The rock (real or artificial) may force a sequence of movement out of me, but it doesn’t tell me what that sequence of movements is, unlike in dance, where a director often teaches a piece of set choreography. I invent it, in response to the problem. Sometimes I may watch somebody else and imitate their movements, but even then, I need to adapt those movements to my body. I ape their movements in general, and then adapt them, precisify their inner feeling, all guided by the difficulties set by the rock. By and large, climbing is a puzzle-and-solution oriented practice. My movements in climbing are always in response to the challenges set to me by the rock; the elegance that I sometimes grasp within myself is one forced on me by the necessities of economy, of preserving what little stamina I have.

Rock climbing is a game. And this is where philosophical work can help us again. Let’s turn to one of the most delightful, insightful, and under-appreciated books in recent philosophy – Bernard Suits’ The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia. You will recall the parable of the grasshopper and the ant – the grasshopper is idle all summer long, and the ant works hard. At the end, the grasshopper starves to death. Moral of the story: work hard or die, suckers. But Suits inverts the moral of the story. In his book, the grasshopper is the hero, a paragon of playfulness. The book opens in adorably pseudo-Socratic fashion. The Grasshopper – the great philosophical defender of play – is on his deathbed, surrounded by his disciples. He is starving because he has refused, on principle, to work. His disciples are begging him: Please, let us feed you, let us work and bring you food. But the Grasshopper replies: No, for then you would be ants, and doubly so! I would rather die for my commitment to idleness!

So the Grasshopper gives his disciples a series of puzzles about play, and games, and then promptly dies. And the rest of the book is one in which the students work out those puzzles, and, along the way, provides a definition of the term “game”. This is explicitly intended as a reply to Wittgenstein’s challenge – that most terms in general, but “game” in particular, did not admit of rigorous definition. Suits offers his definition in versions of varying digestibility. Here’s the least technical one, which he calls the “portable” version:

“Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.”

This gives us a very broad notion of games, which includes board games, sports, rock climbing, and perhaps even certain academic disciplines. Suits’ definition has become rather famous, or infamous, around those corners of the academic world that study games.

In the full version of his definition, we learn, among other things, that playing games involve taking up artificial goals and imposing inefficient means on ourselves, because we want to create a new kind of activity. The point of basketball is not getting the ball through the hoop – that has no independent value in itself. If it did, we’d show up after hours to an empty court with a step-ladder, and pass that ball through to our heart’s content. Rather, we take up the artificial goal – passing the ball through the hoop – and barriers to that goal – opponents, the dribbling rule – in order to create the activity of playing basketball. Notice that what constitutes game-playing is not the physical movement, but the intentional state of the player towards that action. In short: in ordinary practical activity, we take the means for the sake of an independently valuable end. But in gaming activity, we can take up an artificial end for the sake of going through a particular means.

So let’s return to rock climbing. My chosen discipline is bouldering – conducted without a rope, on short boulders of usually no more than twenty feet, with fold-out gymnastics pads to fall on. Bouldering began as a way to train in safety for more adventurous climbs but quickly evolved into its own thing, pursued for its own sake. Boulderers actually refer to specific climbs as “boulder problems”; they are a clear kin to, say, chess problems. Boulder problems are often very short, exceedingly difficult, and the kind of thing you might fail at and fall on your ass a hundred times on the way to success. If those multi-day roped climbs up cliff-sides are the adventure marathons of rock climbing, than bouldering is the sprint trial.

Suits himself uses mountain climbing as an example of a game. The point is not simply to get to the top – after all, you could get to it by helicopter, in the case of Everest, or via the highway up the back, in the case of El Capitan. The point is to do it via a specific set of limited means. This is surely true of bouldering, as well. A regular occurrence for boulderers: we will be trying to climb up the hard overhung face, and a young child will run up the path on the backside of the rock and look down on us from above and gleefully and smugly inform us that we must have missed the easy way up. (Sometimes I have a desire to sit them down and explain the Suitsian theory to them, but usually, since it’s my one day off from grading and the academic slog, I’d just lie down and have a beer.)

So: climbing is a game, in the Suitsian sense. But it is a very interesting sort of game, for many people indulge in it for openly aesthetic reasons. If one looks at the recent history of the philosophy of sport, one will find the Suitsian analysis all over the place, but theorists have considered a fairly narrowed range of reasons for engaging in that Suitsian activity. Usually, it’s something like: we take up these unnecessary obstacles to become more excellent, or develop physical skills, or to win. But the Suitsian analysis allows any sort of reason for wanting to bring an activity into being, and if one listens to the talk of climbers, one will discover that those reasons are often aesthetic ones – and they are often proprioceptively aesthetic.

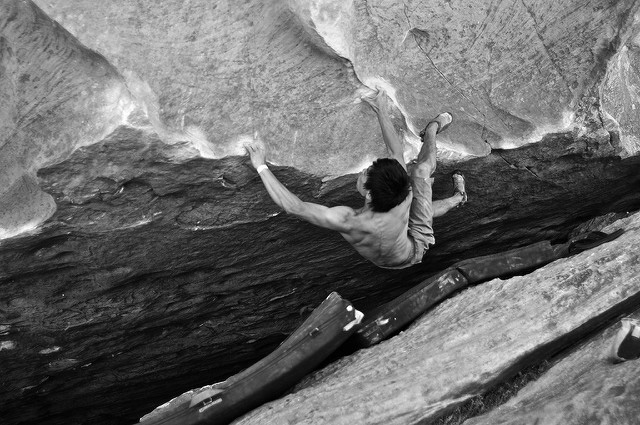

Let’s take one classic climb in Joe’s Valley, Utah: The Angler, one of the most beloved boulder problems in one of the most beloved bouldering regions in the world. As it turns out, it’s not that interesting to watch somebody climb it. First of all, non-climbers tend to like to watch really explosive and spectacular movement. During competitions on artificial rock, lay audiences will cheer for big jumps from one huge hold to another. The Angler has none of that; it’s slow, plodding, and careful. Experienced climbers tend to like watching subtle, intricate movement, but even then, it’s best when the movement is visible – when you can see the re-balancing, the yoga-like stretches, the interesting body postures. But none of the interesting stuff is visible in The Angler. It’s very gradual, delicate climb, with a slopey, slippery ridge for your hands, and tiny invisi-feet. The difference between success and failure depends on minuscule shifts of balance – it depends on maintaining your core tension, on controlling your centre of gravity and inching it around with painstaking care. And, when you do it right, it feels unbelievably good – it feels like you’re a thing made of pure precision, a scalpel of delicate movement, easing your way up the rock. But, to somebody watching from outside, it looks… like nothing. Even for an experienced climber, it’s pretty boring to watch somebody else climb this thing. I love The Anglerto death, but I’ll admit: I’ve sat with a beer by the river next to it and tried to watch people climbing it and gotten bored almost instantly. In this particular climb, all those fascinating internal movements are invisible to the external eye. The aesthetics of movement, here, are for the climber alone.

Simon Li/Flickr

The Angler is an exemplar of a perfect boulder problem, to many a climber’s taste. It has everything. The rock itself is strikingly beautiful. More importantly, what climbers call the line is visually beautiful. That is, the feature on the rock that the climber follows is visually distinctive, and the path of the climb itself is clear and itself striking and lovely. The movement is wonderfully interesting. And best of all, these things match and fit in a pleasing way. In The Angler, the movement quality changes over the course of the problem. It’s intricate and subtle down below, but the movements become bigger and scarier as the line moves up and right. And, when the season’s right, you have to make the last few moves – which are bold but easy – over the river itself. The feel of the movement rises, as the line rises, from delicate to thrilling. Rock, line, and movement all have a wonderful consonance. And when you pull over the top, after all this pain and carefulness, with your nose crammed inches from the rock, staring down searching for the slightly better nubbins of friction – you stand up right into the mouth of a river canyon, running river all around you, wind in your hair and water burbling, and the sensation of victory bleeds into the sensation of wild, free, open nature.

I manage to be pretty focused in doing philosophy, but some of the most focused and attentive I’ve ever been in my life is on a hard climb – mind zeroed in on tiny ripples in the rock for my feet, exactly the angle of my ankle, whether I’m holding the most grippy part of the rock with my hand, the exact level of force I need to push with on my foot as I slide over to the next hold. One might be tempted to say here, if one were caught in a traditional aesthetic paradigm, that the climbing is just a technique, a trick to focus the mind on the really beautiful things – the rock itself, and nature. But I think this ignores what climbers are actually doing, feeling, and appreciating. They’re paying attention to themselves, to their own movements and appreciating how those movements solve the problem of the rock. The aesthetics of climbing is an aesthetics of the climber’s own motion, and an aesthetics of how that motion functions as a solution to a problem. There is, for the climber, a very special experience of harmony available – a harmony between one’s abilities and the challenges they meet.

I remember one afternoon I spent in the Buttermilks, a glorious collection of boulders in Bishop, California. I was trying my damnedest to solve a weird, tricky problem that involved a series of heel-hooks and toe-hooks and spending half-my time with my feet above my head, my ankle stuffed into a crack in the rock. Next to me, a far better climber was working a far harder problem on another part of the same boulder. We spent the whole afternoon at our respective tasks. He was totally, savagely into it – screaming his way up, cursing, stabbing at the rock. The critical move involved easing his way up to a bad, slopey hold for his right hand, high-stepping his left foot up almost to his crotch, and then squeezing himself up between his right hand and his left foot, popping himself between them like a wet watermelon seed, and stabbing with his left hand for a tiny set of pocket dimples. The move is typical of high-end bouldering – the hold you’re going for is so far out of reach that you need to fling yourself at it dynamically; you’ve got to jump. But that hold is also so faint that you can’t have any extra momentum when you hit it, or you’ll rip yourself right off the rock.

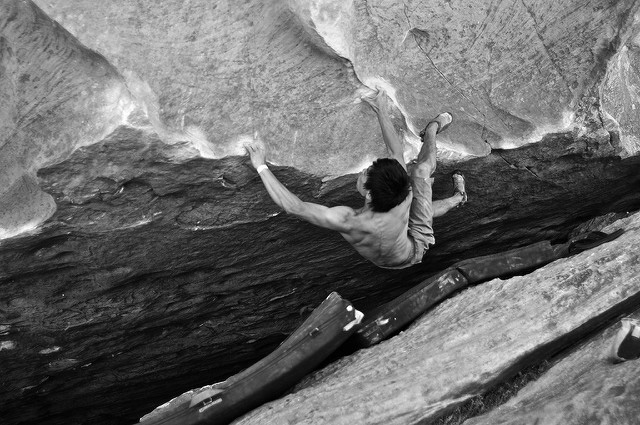

He’d been trying the same move for, like, three hours, with long rests between tries. He was cursing, frustrated, melting down. Then finally, in one great screaming effort, he did it – he had a little bit too much momentum, but he grabbed that next hold with extra force, muscles straining, yanking himself back into place, screaming. And he finished the problem.

He came down, staring at his fingers. One of them was bleeding.

“Nice job”, I said. I went to high five him, but he shook his head.

“That was ugly as hell”, he said, glumly. “Terrible style”. He wrapped up his finger in some climbing tape, rested himself for about twenty minutes, and then stepped up and did again. This time, it looked perfect – just a delicate little bump and step and he floated over and just dropped into place, like it was nothing.

He climbed down the back and jogged over to me, grinning hugely. “God, what a gorgeous problem!” he told me. “You’ve got to do it. That move is so beautiful. It’s just…” he mimed the move, and mimed it again. “Just fantastic! You’ve got to do it!”

Sadly, I told him, that problem was way too hard for me.

He jittered from foot to foot, grinning and trying to feel sorry for me. Then he went over and did it again.

(Originally published in The Philosopher’s Magazine, 78, 2017: 37-43)